by Merle Ratner

CUNY Labor 669

May 22, 2021

Introduction

Anti-communism has played a pernicious role in the development of U.S. racial monopoly capitalism, in general, and in the development of the labor movement, in particular. From the time of the Paris Commune in 1871 to the 1919-20 Palmer Raids to McCarthyism and the Cold War in the 1950s, U.S. governments and capital have utilized anti-communism in attempting to defeat real or imagined threats.[1]

Born in 1956 and coming of age in the mid-1960s, I experienced anti-communism in elementary school, in the “duck and cover” exercises intended to warn and “protect” us in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack. But while this was a dramatic scare tactic, my most memorable example of lived anti-communism occurred when I drew an anti-apartheid cartoon in school and brought it home to show my parents, the daughter of a labor leader in the early garment union and the son of Communist Party members who had been blacklisted during the 1950s. They looked at my drawing approvingly and then hid it deep in a drawer, cautioning me never to mention it to anyone again!

Today, as I explore in the final section of this paper, anti-communism manifests in both familiar and novel ways that still affect both prospects for labor and for Black workers.

My original intention was to write about the relationship between anti-communism, the U.S. labor movement, and Black workers and labor leaders. However, after reading all or part of more than ten books and countless articles, I realize that doing justice to this subject would require a much longer paper and more time than is available to meet the deadlines of this assignment. This is because this relationship (or dialectic) is multi-layered and each element both acts upon and is acted upon by the others.

I decided to approach this area of study by, instead, focusing on oral histories (written autobiographically and transcribed by others) of Black Communist labor leaders who were impacted by, and fought back against, anti-communism and racism during the period between 1945 and the early 1960s (roughly the time of the McCarthy era). This approach will offer more of a feel for the politics, the forces and the contradictions that shaped this consequential period in U.S. history.

One thing I omitted, that begs for further attention, is the international dimensions of anti-communism during this era. It is important to note that the Cold War not only affected workers and the Black working class in the U.S. but had a profound impact on the labor movement and anti-colonial/imperialist struggles abroad. The AFL-CIO, working with the CIA, engaged in a decades long program of subverting Communist, left and independent labor movements and supporting right-wing, U.S. backed regimes the world over, under the auspices of the American Institute for Free Labor Development (built upon the ashes of the Free Trade Union Committee).[2]

After a rough sketch of the period, I focus on three labor leaders: Hosea Hudson, Sylvia Woods, and Jack O’Dell, all of whom were members of the Communist Party. Two of them remained Communist Party members until their death and one left the Communist Party after the McCarthy period because of the threat anti-communism posed to his work in the civil rights movement.

Finally, I address some implications for the contemporary labor movement in which white supremacy and anti-communism (or anti-socialism) is rearing its ugly head again in an effort to beat back the beginnings of a resurgence in class struggle militancy and Black power.

Anti-Communism, Labor and Black Workers

Anti-communism[3] has been a feature of capitalism’s fight against labor since the late 19th century. The capitalist class and their political enablers, employing the ideology of anti-communism, fomented violent raids against organizers and led to labor activists being jailed and executed, as early as the Haymarket martyrs in 1887 and Sacco and Vanzetti in 1927.[4]

My focus here is the period leading to, encompassing and immediately following the McCarthy period – a period where a coordinated process of anti-communism was led by the U.S. government, legislature, courts and business owners, with significant popular support.

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (originally the Committee for Industrial Organization before its split from the American Federation of Labor) – the CIO was formed in 1936 to organize all U.S. workers on an industrial rather than craft basis. In 1946, the CIO and its Southern Organizing Committee launched Operation Dixie, “a million dollar campaign…that was the single largest labor organizing drive ever undertaken in the South.”[5] Its promise, according to historian Michael Honey, rested upon, “a core of activists [who] had struggled for years to change the South from a reactionary bastion of the local elites who used anti-unionism, racism and anti-communism interchangeably to stay in power.”[6] Core among these activists were Black trade unionists who supported the CIO. Having, according to Honey, “fully committed itself to integration…African Americans who worked in the region’s industries, had already become the CIO’s strongest supporters.”[7] This “transformed the labor movement …[and] Black workers left their mark.” The CIO also left its mark on Black workers. The National Negro Congress, formed in the wake of the CIO, aimed at, “supporting [1] industrial unionism and winning over the African American people…”[8]

The left wing unions in the CIO, especially Communist led unions, “had long taken the position that fighting racism and racial division was crucial to any effort to organize workers in the South.” Forming a left-center coalition in the CIO meant that all CIO unions had a basic commitment to anti-discrimination policies and for interracial organizing.[9] While, “all workers gained substantially from the organizing drives of the CIO,” argues historian Philip Foner, “Black workers perhaps gained the most.”[10]

This background should have created rather favorable conditions for organizing the South, the goal of Operation Dixie. But Congress passed Taft-Hartley, requiring non-Communist affidavits for unions that wanted to hold NLRB elections. This law was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in American Communications Assn. v. Douds, 339 U.S. 382 (1950). There were other laws punishing Communists in the labor movement. For example, Section 504 of the Labor Management Reporting Act of 1959 also made it a crime to belong to the Communist Party and to serve as a member of an executive board of a labor union. Hugh Bryson, president of the National Union of Marine Cooks and Stewards, was the first labor leader convicted on perjury charges for lying about his Communist Party membership when filling out the affidavit of non-Communist membership required by Taft Hartley. See, U.S. v. Bryson.[11] He served two years of a five-year sentence in federal prison.[12] This law was ultimately found unconstitutional in 1965 by the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437 (1965).[13]

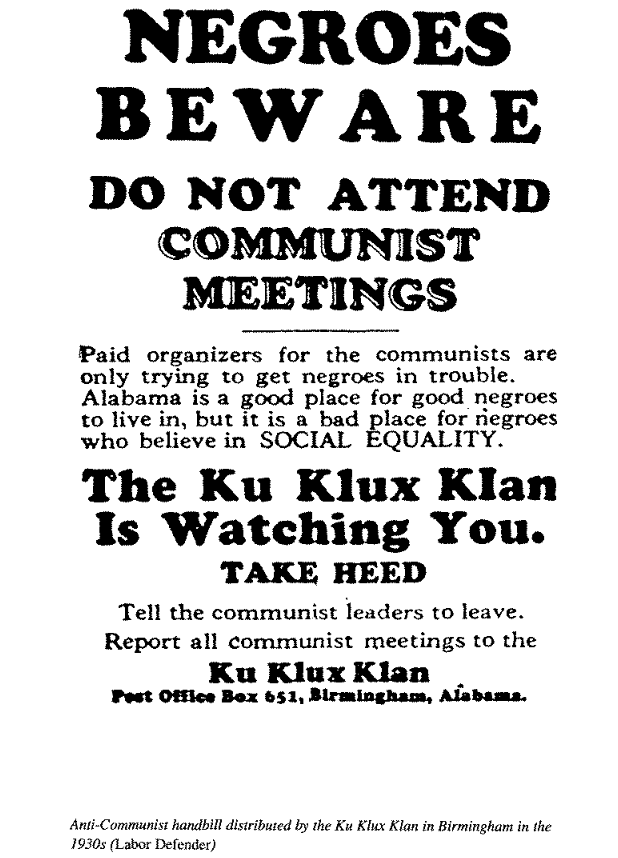

The CIO faced difficult conditions when undertaking Operation Dixie. Even at its beginnings in 1935, business owners attacked the CIO unions and members using propaganda, threats and violence.[14] But with the advent of the “red scare, segregationist upsurge and the Cold War,” it would have taken long-term strategies and “a deep commitment to struggling for Black civil rights,”[15] according to Honey, to overcome the unfavorable objective conditions the CIO faced in the South. “State legislatures and city councils passed…anti-union ordinances.” “The re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan galvanized the anti-union campaign” and violence and the requirement to file anti-Communist affidavits with the NLRB were other barriers.[16] In addition, many white workers joined racist organizations in an attempt to maintain workplace segregation and priority in jobs and seniority.[17]

But the CIO contributed to its own defeat as well. After the election of Truman to the Presidency in 1948 and the start of the cold war, left-center unity began to shatter. In the South, with the growth of anti-communism (and its link to white opposition to civil rights), the CIO placed staunch anti-Communists in the leadership and staff of Operation Dixie. They looked for quick victories, according to Honey, through the use of “flying squadrons,” rather than digging in for the kind of sustained organizing that was necessary.[18] They also focused their organizing on the predominantly white textile sector rather than on other industries where Black workers predominated.[19] There was often a distinction in the CIO between rhetorical anti-racism and anti-racist action wherein, “many CIO unions maintained separate seniority lists, Black and white, and had differences in participation in decision-making and union office holding.”[20]

Essentially, “anti-communism was also a veil for racism,” historian Robin Kelley concludes.[21] The conservative CIO leaders were “soft” on fighting racism which weakened the ties between the CIO and Black workers.[22] By 1950, an African-American magazine decried the practice of racism in CIO unions in the South, describing the common practice of CIO union halls with, “Jim Crow toilet facilities.”[23]

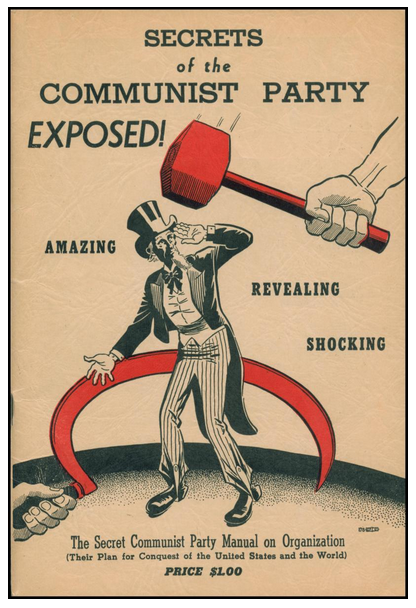

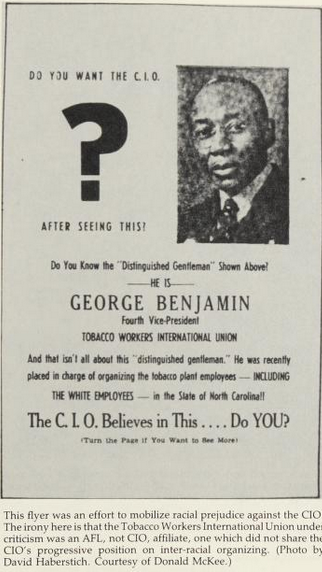

Unions in the CIO began to attack and purge left and Communist unions. In 1947, a year and a half after the beginning of Operation Dixie, the CIO began to raid Communist-led unions like Local 22 of the Food and Tobacco Workers Union.[24] Another union, The Mine Mill Union, “had to fight off a raid by the combined forces of the Ku Klux Klan and the United Steelworkers who were attempting to break up this union.” Many unions with large Black memberships were subject to this raiding, an example of, “how far the once militant CIO had deteriorated” to the point where it adhered to a policy of “anti-Communism, the policy dictated by the industrialists.”[25] (See examples of anti-Communist leaflets in the Appendix.[26]) The CIO, at its convention in 1949 expelled eleven left unions, with over a million members, “for refusing to cooperate with the anti-Communist purge.”[27]

The placement of anti-Communist leaders in leadership roles in Operation Dixie and the associated purging of Communist CIO unions in the South not only deprived the labor movement of its most dedicated and disciplined organizers (including many Black organizers) but it also deprived Black workers in the South, according to Kelley, of a, “working class alternative to the NAACP”[28] – what was essentially, “a southern, working class Black organization.”[29]

These leaders made serious errors by “marginaliz[ing] leftists and interracial activities” which made it near impossible to succeed in organizing the South.[30] One legacy of this is that when Communists, “were expelled, [from the CIO] much of the Black-white unity also departed.”[31]

This does not mean that all CIO unions had given up their militancy, anti-racism, and democratic principles. United Farm Equipment Workers Local 236 (“FE”) at International Harvester in Louisville, Kentucky had a history of racial solidarity in theory and in practice, with a, “constant campaign to unite the Louisville workforce.”[32] FE was expelled from the CIO in the 1949 purge.

An unsuccessful Operation Dixie, according to The Crisis, “died in 1946 when the organizing staff was cut in half…and was officially closed in 1953.”[33] The stories of leading Black Communist CIO organizers illustrate both the promise and the limitations of Southern labor organizing in this period.[2]

Oral Histories

Hosea Hudson

Hosea Hudson was born in rural Georgia in 1898. Illiterate at the time, until he learned to read with the help of Communist comrades, he worked as a sharecropper, laborer and then as an iron molder in Birmingham. He joined the Communist Party in 1931. In 1932 he was fired from the Stockham Foundry on suspicion of being a Communist. In 1942, he became the President of Steel Local 2815 and delegate to the Birmingham Industrial Union Council. He was expelled from the Council and his job and from his union presidency in 1947. He remained a life-long Communist until his death.[34]

Hudson was working at the Smithfield plant in Birmingham as a member of the CP industrial club in 1947. He was giving out copies of the Daily Worker when he was told by the VP of the union local that the boss, “don’t want no more of these Communist newspapers in the shop.” After this announcement, his fellow workers stopped coming to meetings.[35]

In 1947, Hudson was an active member of the Birmingham Industrial Council (made up of delegates from CIO locals). In October 1947, the Birmingham Post carried an article that suggested “Hosea Hudson, president of Local 2815, works at Jackson Foundry Industrial Plant, is suspicious of being a member of the Communist Party of the United States, and also a member of its National Committee.” Hudson says that his local members, particularly the Black members who were the ones attending union meetings (although he says there were a few “rats” among the Black members as well,) didn’t care about the article, as one of them remarked: “Hell I don’t care what Big Red is. Damn, he’s my man, cause he gets things done here, better conditions, better wages we wouldn’t have had it if it hadn’t been for him.”[36]

Charges of being a Communist were brought against Hudson in the Council in 1947 by the president of the TCI hospital workers, who was white. Hudson defended himself on First Amendment grounds, but the Council voted to eject him. While a small minority of Black workers voted against him, the majority supported him and it was the votes of the white members that caused his removal.[37] When Hudson tried to go back to the next Council meeting, his way was blocked by a white member of the Steelworkers Union who was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[38] The final blow came when Hudson was fired from his job at Jackson Foundry Industrial Plant because some workers signed a letter refusing to work with him. This was initiated by white union workers who didn’t want Williams to be president of the local and the Steelworkers Union District office put them “up to doing it.” The letter was signed by many Black workers because the white workers asked them to sign a blank sheet of paper supposedly for seniority rights. After they signed, the white workers wrote the letter urging Hudson’s dismissal above the signatures.[39]

Hudson grieved his termination but at the final step, the arbitrator was a segregationist and upheld his firing. After his firing, Hudson had to resign as president of the local.[40] When the contract came up for negotiation, the local president was told by the district office leaders to ask for less than half of what the workers wanted, in exchange for bribes to the union officials. When the workers found out what had been planned, the white workers went to the United Steelworkers District Office and told them that they didn’t want district union staff coming out to the plant or the local, saying, “Your men had us to sign Hosie Hudson out of that plant.”[41]

Hudson was engaged in trying to get Black voters registered in the Jim Crow South. When he raised the issue of pushing for registration of Black voters at a meeting chaired by the state president of the CIO, the man deflected the question. Hudson pointed out the contradiction of trying to build the labor movement while ignoring civil and human rights for Black people. “We got to get the white members to take a more active part in trying to help the Negro members pass the Board of Registrars….It’s like trying to fight with one hand tied down side of you. Here you fight with one hand, the other hand tied is the Negro…Automatically the Negro gets the vote, he automatically will support labor candidates.”[42]

Hudson credited his participation in the Communist Party for his ability to fight and win: “That was something wont it? Them the kind of fights I put up. It was the Communist Party that learnt me that.”[43]

Sylvia Woods

Sylvia Woods was born in New Orleans in the early 1910s to a Garveyite father who was a union man. She married young and then moved to Chicago. She began her activism by refusing to sing the Star Spangled Banner and recite the pledge of allegiance at school because she could not play in a white’s only park near her school.[44] She worked in a laundry where she “spearheaded the organizing for the Laundry Workers Union.”[45] However, when the union representative came to the Brooks laundromat to report on their bargaining with management, they had signed a first contract for less than what the women were already making. Woods says, “I got mad and quit the union…I just pulled out the whole Brooks laundry.” When confronted by the union official, she responded, “I’m not coming back because you had no business to negotiate the contract. You should have brought it to us first.”[46]

She then went on to work at Bendix Aviation, an airplane parts factory, and was active in the United Auto Workers local. Shortly upon being hired, she was elected steward and then committeewoman.[47] Of note is the fact that, as a leader in the UAW local at Bendix, Woods took part in building a democratic local, which, “did not want dues check-off, feeling that it would dampen voluntary participation by the membership,” and conducted regular labor education at union meetings.[48]

Woods later went on to work as a Licensed Practical Nurse at Cook County Hospital. She ran for Illinois State representative in 1946, the first Black woman to run for that position. She fought against the Smith Act and McCarthyism and co-founded the Black Panther Party’s free clinic and breakfast program as well as working to free Angela Davis and co-founding the National Alliance Against Racism and Political Repression. [49]

Before she became a Communist, Woods believed that there was no basis for unity among Black and white workers because of the white supremacy she had witnessed. She says, “I only joined the union for what it could do for Black people; I didn’t care anything about whites.”[50] Woods learned, from political education and from organizing as a Communist on the ground, that real solidarity between Black and white workers was both possible and necessary.[51]

Jack O’Dell

Jack O’Dell was born in Detroit on August 11, 1923. He joined the Merchant Marines and the National Maritime Union during World War II and was a seaman for most of the 1940s. He went back to the South in 1946 to organize restaurant workers in Miami Beach as part of Operation Dixie. When O’Dell organized integrated picket lines to support a strike, “the lead CIO organizer…agreed to shut down strike activity after a local sheriff warned that the integrated picket lines O’Dell had helped to organize would lead to violent reprisals…”[52] In 1950, O’Dell was expelled from his union – the National Maritime Union – for circulating a petition for peace and trade with Eastern Europe (to increase jobs for workers) and for supporting Ferdinand Smith, a leftist (and former president of NMU) for president of the NMU against an anti-Communist candidate. He joined the CPUSA waterfront section that year. O’Dell says that Black workers joined the CP, “…because the Communists had an interpretation of racism as being grounded in a system and they were with us…The great reality of my generation was segregation, fascism and colonialism. The Communists were on my side in all of those things.” [53]

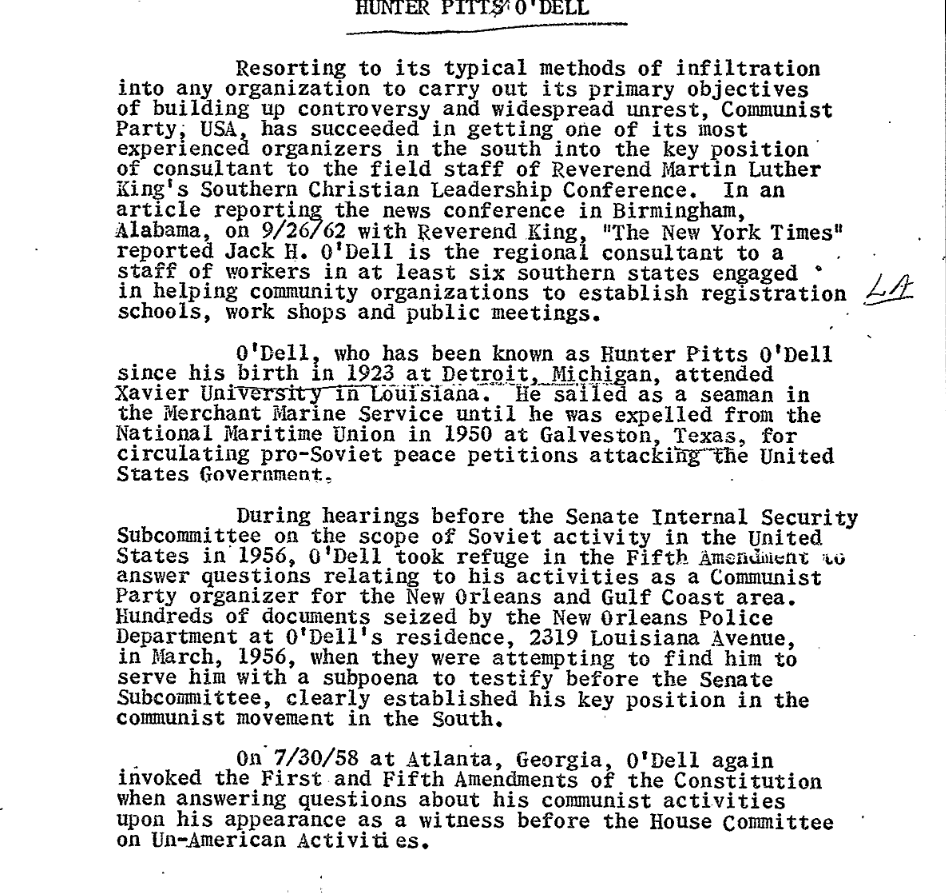

No longer able to work on ships, O’Dell spent the early 1950s doing voting rights work and organizing sharecroppers and cookie manufacturing workers.[54] In 1956 O’Dell was subpoenaed by the Eastland Committee (a congressional committee investigating communism in the U.S.) and refused to testify, asserting his 1st Amendment rights. The Eastland Committee called him again in 1958 and he again refused. Sometime in 1960, O’Dell decided to leave the CPUSA, not because he disagreed with its politics, but because he thought membership would discredit him from being useful to the civil rights movement and was, “putting other people at risk.”[55] This would come to be prescient when he was hired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to work as a key aide and head of the SCLC Harlem office.[56] A close confidant of Dr. King’s he was nonetheless dismissed in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy asked King to fire O’Dell and another left civil rights leader because of their supposed Communist sympathies.[57] (See Appendix below for an example of FBI memos targeting O’Dell.) O’Dell also says that the NAACP, which, in most areas had been against Communists in the civil rights and labor movements, was jealous of Martin Luther King, Jr. and was trying to discredit the SCLC’s focus on direct, mass action.[58]

What These Oral Histories Tell Us

All three of these labor leaders experienced racism and anti-communism in the course of their organizing and, through their courage, dedication and training, were able to organize Black workers in significant numbers. All engaged in the type of militant, democratic union building that typified the best of the CIO tradition. The Communist Party, and especially its Black cadre, played a major role in educating and inspiring these remarkable people.

All three organizers had to struggle, in their own way, to overcome white supremacy and to organize both Black and white workers. Doing this with sometimes racist white workers required extraordinary discipline and self-control that was learned from other Communist organizers.

And each of them had their lives and their labor organizing severely affected by anti-communist laws, white supremacy and the CIO purges of Communist and left unions. Yet each of them went on to a lifetime of work for class and social justice and for Black liberation. Their stories are a tantalizing look at what could have been if the CIO had not succumbed to anti-communism and racism in its final stage!

Jack O’Dell is the person who lived the longest, dying only in 2019. He continued to be a leading activist and movement theoretician until the end, focusing on building united front politics and organization. He initiated and led the Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition and was working on a successor project: The Democracy Charter, in his last years.[59] But for the most part, in later years, without a revolutionary organization, O’Dell was forced to arrange his own work, project by project. One can only imagine what O’Dell, as part of a truly revolutionary communist party, would have been able to create! This is one of the unspoken tragedies of the deadly cocktail of anti-communism and white supremacy that we continue to live with.

Thoughts about Today’s Labor Movements

The failures of Operation Dixie and the destruction of the CIO loom large upon today’s labor movements has many contemporary parallels.

The subsequent domination of the class collaborationist, anti-communist, racist and xenophobic AFL-CIO has contributed to a shrinking not only of the percentage of unionized workers and the overall power of labor, but of the very idea of the working class itself. This has often been replaced with the vague concept of a “middle class” accompanied by a “lower class” that has been racialized and demonized. Pride in being working class has been replaced, for many, by the ideal of entrepreneurship. The deformed and dystopian Trumpist concept of blue-collar workers has captured a segment of white (and some not white) people as an alternate way of seeing “class.”

But one thing that this paper makes clear is that, under the current state of neoliberalism (or whatever it may be morphing into) there is neither a winning labor movement nor a conscious working class without unyielding opposition to white supremacy and racism. (The same is true for male supremacy and sexism, but that is the subject of another paper.)

While all labor unions today pay lip service to anti-racism, many honor this only by its absence. This was illustrated by our study of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and there are many current examples. My discussions with union members in the construction trades, for example, elicit descriptions of how union corruption and racism combine to deny Black workers jobs, well-paid work, and safety on the job.

Racism also affects those who are considered workers and who is eligible for the protection of labor laws. Nationally, farm and domestic workers are still not covered under the NLRA. Just this month, in New York State, draft legislation, supported by the NYS AFL-CIO, was introduced in the legislature that would deny app-based workers employee status. This bill builds on the Machinist Union’s yellow union, Independent Drivers Guild, which is controlled and paid for by Uber. It would deny the overwhelmingly Black and brown taxi and food delivery workers genuine unions of their choice in favor of government-chosen unions that would be barred from “picketing, striking, slow downs or boycotts.” If passed, this legislation would also remove local governments’ power to legislate minimum wages or working conditions for app workers. Clearly this is a huge give-away to some of the largest corporations in the world at the expense of precarious Black and brown workers[60] and yet another shameful chapter in the history of the AFL-CIO (at least in NY State – other state councils have taken better positions on gig worker issues).

Another parallel is the increased number of workers joining right-wing organizations, with updated anti-communist propaganda. While some of this is aimed at a perceived threat from China, much of it relies on old racist, anti-communist tropes.

The many lessons from the period of the CIO and Operation Dixie are too numerous to detail here, but if we are to build a powerful, successful and united labor movement to propel us forward into a viable future, these lessons must be further studied, learned and acted upon!

Final Paper Grade: A

*** This version was proofed by Juliet Ucelli and Ngô Thanh Nhàn and incorporated comments and suggestions from Professors Stephen Brier and Ellen Dichner

ENDNOTES

Appendix

FBI Memo on Jack O’Dell:

Materials “Exposing” Anti-Communism in the Labor Movement:

According to much of the material, labor unions were ripe for Communists to infiltrate, with one of their most important goals being the ultimate seizure of power. Communists were the “con men” of the labor movement, and it was the responsibility of employees to resist Communist influence through loyalty to capitalism and democracy, having confidence in one’s future, and undermining Communist ambitions.

From Con-Men of the Labor Movement: Communists and Labor Unions website

From The Crisis of American Labor, Page 123 and 131

From Hammer and Hoe, Page 75

Bibliography

American Communications Assn. v. Douds. 1950, 339 U.S. 382.

Boggs, James. 1963. History Is a Weapon, The American Revolution: Pages From a Negro Worker’s Notebook. New York: Monthly Review Press. https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/amreboggs.html.

Buhle, Paul. 2011. “The Jack O’Dell Story.” Monthly Review (New York, N.Y.: 1949) 63 (1): 48.

Clark, Christopher, Hewitt, Nancy, Roy Rosenzweig, and Nelson Lichtenstein. 2021. “The Red Scare and American Civil Liberties.” Who Built America, Working People and the Nation’s History, Vol. 2, Chapter 6. 2021. https://wba.ashpcml.org/wars-democracy-1914-1920.

DeManuelle-Hall, Joe. 2021. “Draft Legislation in New York Would Put Gig Workers into ‘Toothless Union.’” Portside. May 22, 2021. https://portside.org/2021-05-22/draft-legislation-new-york-would-put-gig-workers-toothless-unions.

FBI. n.d. “Jack O’Dell FBI File.” Jack Odell Fbi File from the National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/jfk/releases/docid-32989661.pdf.

Fletcher, Bill, Jr, and Peter Agard. 2000. “The Indispensible Ally: Black Workers and the Formation of the CIO.” The Dispatcher. http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/336.html.

Foner, Philip S. 1974. Organized Labor and the Black Worker 1619-1981. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Gilpin, Toni. 2020. The Long Deep Grudge: A Story of Big Capital, Radical Labor, and Class War in the American Heartland. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Goldfield, Michael. 2020. The Southern Key: Class, Race, and Radicalism in the 1930s and 1940s. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Griffith, Barbara S. 1988. The Crisis of American Labor: Operation Dixie and the Defeat of the CIO. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Grijalva, Brian. 2009. “Communism in Washington State, Organizng Unions: The 30’s and 40’s.” Communism in Washington State, History and Memory Project. 2009. https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/cpproject/grijalva.shtml.

Guttenplan, D. D. 2014. “Who Is Jack O’Dell.” The Nation, 2014.

Haywood, Harry. 1978. Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Communist. Chicago, IL: Liberator Press.

Honey, Michael K. 2004. “OperationDixie, the Red Scare, and the Defeat of Southern Labor Organizing.” In American Labor and the Cold War, edited by Cherney, Robert W, Issel, William and Taylor, Kieran Walsh. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Kelley, Robin D. G. 1990. Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Lynd, Alice, and Lynd Staughton. 1973. RANK AND FILE Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. https://assets.ctfassets.net/xfu8r0n4zgvn/6XVToErgF4YeiKz79yE8Fg/504494ddc1120580c62b048dbcb321a4/Alice_and_Staughton_Lynd_-_Rank_and_File__Personal_Histories_by_Working-Class_Organizers-Haymarket_Books__2012_.pdf.

Naison, Mark. 1983. Communists in Harlem during the Depression. Baltimore, MD: University of Illinois Press.

O’Dell, Jack. 2010. Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder: The Black Freedom Movement Writings of Jack O’Dell. Edited by Nikhil Pal Singh. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

———. n.d. “Jack O’Dell Oral History.” Tamiment Library Communist Party Oral Histories, Jack O’Dell. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://wp.nyu.edu/tamimentcpusa/collections/tamoh/jack-odell/.

Painter, Nell Irvin. 1979. The Narrative of Hosea Hudson: His Life as a Negro Communist in the South. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Press, Alex N. 2021. “The Alabama Amazon Drive Could Be the Most Important Labor Fight in the South in Decades.” Jacobin, 2021. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/02/amazon-unionize-alabama-operation-dixie-organizing-south.

Roediger, David. 1992. “Where Commmunism Was Black.” American Quarterly 44 (1): 123–28. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/15219/Roediger_When_Communism_Was_Black.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Ruch, Walter W. 1946. “Rival of AFL, CIO Attacks Leftists.” The New York Times, September 22, 1946.

Sandomir, Richard. 2019. “Jack O’Dell, King Aide Fired Over Communist Past, Dies at 96.” New York Times, November 19, 2019.

Scanlan, Alfred Long. 1953. “Communist Dominated Union Problem.” Notre Dam Law 28 (4): 457–96. https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3724&context=ndlr.

Schuhrke, Jeff. 2020. “To Build a Left-Wing Unionism, We Must Reckon With the AFL-CIO’s Imperialist Past.” Workplace Fairness. January 13, 2020. https://www.workplacefairness.org/blog/2020/01/13/to-build-a-left-wing-unionism-we-must-reckon-with-the-afl-cios-imperialist-past/.

Smith, Philip. n.d. “Seeing Red: A Historiographical Study of the American Communist Movement During the Interwar Period.” TWU Education. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://twu.edu/media/documents/history-government/Seeing-Red-A-Historiographical-Study-of-the-American-Communist-Movement-During-the-Interwar-Period.pdf.

United States v. Brown. 1965, 381 U.S. 437.

United States v. Bryson. 1968 403 F.2d 340 (9th Cir. 1969).

Unknown. 2019. “Con-Men of the Labor Movement: Communists and Labor Unions.” https://www.hagley.org/research/programs/nam-project-news/con-men-labor-movement-communists-and-labor-unions.

UPI. 1984. “Hugh Bryson, Union Official.” The New York Times, May 23, 1984.

Woods, Wyatt and Durham Memorial Foundation. 2019. “Sylvia Woods Biography.” WOODS, WYATT AND DURHAM MEMORIAL FOUNDATION. 2019. https://www.wwdmf.org/sylvia-woods.

[1] Who Built America, Working People and the Nation’s History, Vol. 2, Chapter 6

[2] To Build a Left -Wing Unionism We Must Reckon With The AFL-CIO’s Imperialist Past

[3] While the term anti-communism is used mainly to refer to members and activities of the Communist Party USA I also use it in this section to include its application to anarchists and socialists.

[4] Who Built America, Vol. 2, Chapter 2, 1886- The Eight Hour Movement and Haymarket Square

[5] Operation Dixie, the Red Scare, and the Defeat of Southern Labor Organizing.” In American Labor, Page 222

[6] Operation Dixie, Page 216

[7] Operation Dixie, Page 217

[8] The Indispensable Ally: Black Workers and the Formation of the CIO, Page 216

[9] Operation Dixie, Page 218

[10] Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981, Page 231

[11] United States v. Bryson. 1968 403 F.2d 340 (9th Cir. 1969)

[12] Hugh Bryson, The New York Times, May 23, 1984

[13] United States v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437 (1965)

[14] The Crisis of American Labor, Page 97-100

[15] Operation Dixie, Page 221-22

[16] Operation Dixie, Page 225

[17] Operation Dixie, page 236

[18] Operation Dixie, page 221

[19] Operation Dixie, page 228

[20] The Crisis of American Labor, page 86

[21] Hammer and Hoe, Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, page 141

[22] Operation Dixie, page 226

[23] Organized Labor and the Black Worker, page 292

[24] The Crisis, Page 145-53

[25] Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, Page 245

[26] Con-Men of the Labor Movement, Page 1

[27] Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, Page 35 (not sure about whether page numbers in Nook are correct)

[28] Philip Foner points out that that, “the leaders of many local NAACP branches had formed close alliances with employers and were opposed to all union.” Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981, page 217

[29] Hammer and Hoe, page xii

[30] Operation Dixie, page 230

[31] Organized Labor, page 292

[32] The Long Deep Grudge, Location 4312 (I couldn’t locate the page numbers in Kindle)

[33] The Crisis, Page 161

[34] The Narrative of Hosea Hudson: his life as a Negro Communist in the South, Page xiii-xiiii

[35] The Narrative, Page 311-12

[36] The Narrative, Pages 352-3

[37] The White Narrative, Page 353-4. The white members represented locals with significant numbers of Black members and had more votes because of the size of their memberships, however Black members of those locals were only dues paying members and had no say in the way their representative voted.

[38] The Narrative, Page 365-56

[39] The Narrative, Page 357-58

[40] The Narrative, Page 359-60

[41] The Narrative, Page 360-61

[42] The Narrative, Page 332-33

[43] The Narrative, Page 362

[44] Rank and File, Personal Histories by Working Class Organizers, Page 115-16

[45] Woods, Wyatt and Durham Memorial Foundation, Woods Biography, Page

[46] Rank and File, Page 122

[47] Rank and File, Page 126

[48] Rank and File, Page 111

[49] Woods, Wyatt, Woods Biography, page

[50] Rank and File, 124

[51] Rank and File, 127-28

[52] Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, Page 27-28 (not sure about whether page numbers in Nook are correct)

[53] Climbin’ Jacobs Ladder, Page 39

[54] Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, Page 35-37

[55] Jack O’Dell Oral History, Tape 2

[56] Who is Jack O’Dell

[57] Jack O’Dell, King Aide Fired Over Communist Past, Dies at 96

[58] Jack O’Dell Oral History, Tape 2

[59] Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, See chapter: The Democracy Charter

[60] Draft Legislation in New York Would Put Gig Workers into “Toothless Union”